Mind The GAAP: How loss-making companies adjust numbers to show they are profitable

Several new-age companies—listed as well as privately held—resort to accounting acrobatics to make their earnings appear more palatable. Though 'adjusted' and non-GAAP metrics can't be questioned legally, pro-forma earnings tend to put the entities on a morally sticky wicket

There were more creative expressions to numb your financial senses

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

There were more creative expressions to numb your financial senses

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

Let’s start with the kindergarten stuff. What does ‘A’ stand for? The most popular answer would be 'apple’. Can the same alphabet, and question, have a different reply? Yes, if the ones answering happen to be smart alecks! To them, ‘A’ might be ‘awesome apple’ or ‘American apple’ or ‘accomplished apple’. Apple certainly can have endless variants.

Back in 2018, America was getting a taste of Adam’s apple. A smart aleck, WeWork’s co-founder and CEO Adam Neumann, stunned the world by reportedly displaying a wide range of accounting stunts in the bond-offering document released in April. Sample the most ingenious and outrageous term: ‘Community-adjusted Ebitda’. The metric measured net income before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation, and ‘building-and community-level operating expenses’, which reportedly includes rent, tenancy expenses, utilities, internet, salaries of building staff, and the cost of building amenities.

There were more creative expressions to numb your financial senses. ARPPM (annual average membership and service revenue per physical member), adjusted Ebitda before growth investments, and location contribution happened to be some of the gems devised by WeWork. To be fair, Neumann was not alone in resorting to non-GAAP metrics in reporting earnings.

GAAP stands for ‘generally accepted accounting principles’. According to Investopedia, GAAP refers to a common set of accounting rules, standards and procedures which public companies in the US must follow while preparing financial statements. While the most common accounting principle globally is IFRS (International Framework for accounting Records and Financial Statements), the one followed in India is Ind-AS, which is the Indian version of IFRS and quite close to the US GAAP. Creative accounting—like the one done by WeWork—falls under non-GAAP accounting, which makes the earnings release look more attractive.

Back in the US, Neumann was not the only one showcasing his version of ‘apple’. In 2015, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, which reportedly had been using non-GAAP metrics for years, released its financial numbers. While the company reportedly had a GAAP loss of $291.7 million, it reported an ‘adjusted’ non-GAAP profit of $2.84 billion after stripping out amortisation of intangible assets, acquisition costs and other expenses. The same year, another US company reported two sets of interesting numbers. Online lender LendingClub reported a GAAP loss of $5 million, but non-GAAP net income of $56.8 million.

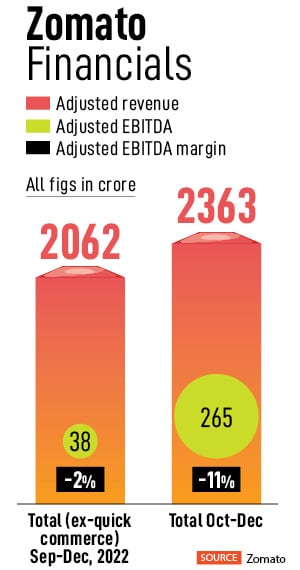

“Zomato is loss making,” says Swapnil Potdukhe, internet analyst at JM Financial Institutional Securities. The reason, he cites, is the high cash burn in business segments like Blinkit, Hyperpure and dining out. “However, food delivery, which is the core segment, is profitable. This is where the profit will come when it scales up,” he adds.

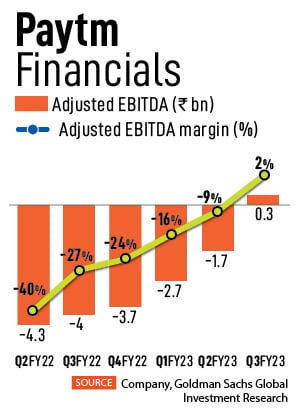

“Zomato is loss making,” says Swapnil Potdukhe, internet analyst at JM Financial Institutional Securities. The reason, he cites, is the high cash burn in business segments like Blinkit, Hyperpure and dining out. “However, food delivery, which is the core segment, is profitable. This is where the profit will come when it scales up,” he adds.  Interestingly, a set of analysts are not perturbed by the ‘adjusted’ profitability metric. “We see Paytm reporting adjusted Ebitda profitability as a significant catalyst for the stock, and expect net income profitability in FY25,” Goldman Sachs maintained in its report.

Interestingly, a set of analysts are not perturbed by the ‘adjusted’ profitability metric. “We see Paytm reporting adjusted Ebitda profitability as a significant catalyst for the stock, and expect net income profitability in FY25,” Goldman Sachs maintained in its report.